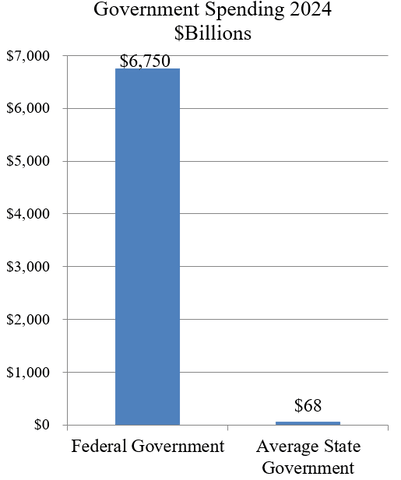

At the end of 2017, Republicans cut the federal corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent as part of a larger package of tax cuts and reforms. Many Democrats—including Kamala Harris—and some Republicans want to raise the rate next year. Former President Donald Trump proposed further cutting the rate to 15 percent.

If taxes on businesses are primarily paid by their owners, corporate tax increases could be a way to raise revenue from higher-income Americans. However, if the economic cost of the tax is ultimately shifted to labor, raising the corporate tax will penalize workers, hurting lower-income Americans the most.

The best economic evidence suggests that workers pay more than half, and likely three-quarters, of the cost of the corporate tax. Thus, cutting business taxes is a tax cut for working Americans.

Why Workers Pay Most of the Corporate Tax

Who bears the ultimate economic cost of a tax is not always straightforward. Employer payroll taxes, for example, are paid to the government by the business, but most of the actual economic cost of the tax is borne by workers through lower wages. The ultimate burden of corporate income taxes also shifts from the entity that pays the government.

Only people can pay taxes, and for the purposes of economics, corporations are not people. In theory, the tax can be paid in one of three ways: by the firm’s owners through lower returns on their investments, consumers through higher prices, or workers through lower wages. The precise distribution of the corporate tax on these three categories is the subject of a long-running and evolving line of economic research.

In 1962, Arnold Harberger first described how, in a closed economy, the corporate tax reduces dividends and lowers investment returns, impacting capital owners the most. However, the results of the Harberger model were upended as globalization and capital mobility between countries increased in the following decades. As I explained in 2017:

In an open economy where capital can move abroad and the prices of goods are set competitively in the world market, the corporate tax has only one place to shift: to workers. When capital moves abroad, the domestic capital-to-labor ratio declines, slowing productivity and lowering wages. The global after-tax return to capital is largely unchanged, but because workers are generally not internationally mobile, wages remain depressed in the country with the higher corporate tax and lower levels of investment.

A related body of research on the relationship between capital and labor implies that when capital per worker rises by 1 percent, wages rise by the same amount or more. In a review of the empirical literature on the incidence of the corporate income tax, Steve Entin concludes, “These studies appear to show that labor bears between 50 percent and 100 percent of the burden of the corporate income tax, with 70 percent or higher the most likely outcome.” No one study is perfect or perfectly applicable to the United States, but the sum of the empirical literature clearly concludes that workers bear a majority of the corporate tax.

Could Workers Pay More than 100 Percent of the Corporate Tax?

The economic damage (what economists call the deadweight loss) of taxes is often larger than the tax revenue collected by the government. In addition to raising revenue, taxes also change behavior, incentivizing people to invest, save, and work less than they would have otherwise. Thus, the revenue raised by the corporate income tax—or any other tax—is a lower bound for the total economic cost of the tax.

Economists Christina and David Romer found that a $1 tax increase in the United States has historically decreased GDP by about $3. Entin notes that widely accepted estimates of labor’s share of output imply that labor pays about $2 of the total economic cost or 200 percent of the $1 tax increase. Corporate income taxes are even more economically damaging than the average result from Romer and Romer, which lumps many types of tax increases together.

If the corporate income tax’s economic cost is multiple times the tax’s revenue, labor can bear more than 100 percent of the revenue raised by the tax. Some studies have found that labor could bear as much as 400 percent of the revenue cost of the corporate income tax. When taxes are highly economically distortionary, there is no shortage of economic costs to be shared by all sectors of the economy.

Recent Empirical Estimates and the TCJA

Disentangling the economic effects of a specific policy change is always empirically challenging, which is why most studies aggregate the impact of multiple policy changes over time. The long-run economic effects of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) were also confounded by concurrent deregulation, economic uncertainty from Trump’s trade policies, and the economic effects and policy response to the pandemic.

Attempting to tease out some of these different effects, two economic studies have used differences in how firms were impacted by the business tax cuts to estimate its short- and long-run effects. Using different methods, Patrick Kennedy et al. and Gabriel Chodorow-Reich et al. both find that the 2017 corporate tax cut resulted in a business investment bump that is in line with the previous literature. According to the authors, the Chodorow-Reich results imply a 0.9 percent long-run increase in GDP from the corporate tax cut and an increase in labor income of about $700 per employee (in 2017 dollars).

Kennedy et al. find a similar short-run increase in c‑corporation wages of about 1 percent compared to s‑corporations, with most of the gains accruing to higher-income employees. This relative wage response between firm types does not account for aggregate wage gains shared across the whole economy or the long-run wage response.

Less sophisticated economy-wide estimates show that average production and nonsupervisory workers—who tend not to be the highest-income employees—saw about $1,400 more in above-trend annualized earnings after 2017 and before the pandemic disruptions.

While short-run results are informative, the expected wage gains from corporate tax cuts are a longer-run phenomenon that results from the additional investment boosting workers’ productivity. Workers are more productive when they have more and newer tools to work with. The long-standing connection between investment, worker productivity, and pay means that the measured tax-cut-induced investment bump will continue to result in widely shared wage gains for years to come.

Economists will continue to debate the magnitude and distribution of investment, wage, and economic growth effects from tax cuts, but it is clear that tax cuts cause improvements in all three economic measures. The opposite is also true: tax increases will depress wage growth, investment, and the broader economy.