Federal government debt is rising to dangerous and unprecedented levels. Without reforms, federal debt held by the public will grow from 98 percent of gross domestic product this year to 115 percent a decade from now. Compared to the size of the economy, federal debt and interest costs are headed toward levels never seen in our nation’s history.

The recent bipartisan debt‐ceiling deal modestly slowed the flow of red ink, but larger reforms are needed. A growing number of fiscal experts are recommending that Congress limit federal debt to 100 percent of GDP (e.g. here, here, and here). That is, Congress should restrain the budget so that debt grows no larger than the economy.

Let’s look at four reasons to cut debt and then examine a plan to hit the 100 percent target with entitlement and federalism reforms.

Four Reasons to Cut Federal Debt

Funding spending with debt pushes costs onto young people in the future. But young people will have their own costs, crises, recessions, and wars to deal with, so burdening them with our costs in addition is unjust.

High and rising debt increases macroeconomic instability, and it will likely prompt a major financial crash and recession, which will cause hardship for many and undermine living standards.

Many statistical studies have found that government debt above about 90 percent of GDP slows economic growth.

Most federal spending goes toward subsidy and aid programs, which help recipients but distort the economy. As such, reducing debt with spending cuts would boost growth as resources were reallocated to higher productivity uses.

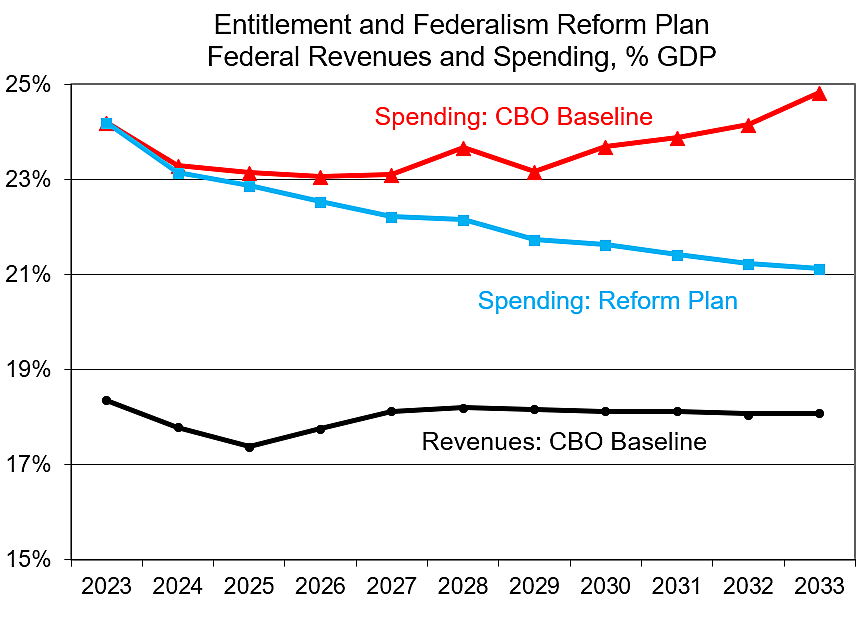

Excessive spending is causing the surge in debt. As shown in the chart, CBO expects federal revenues to remain at about 18 percent of GDP in coming years, a bit above the 50‐year average of 17.4 percent. The problem is that spending is projected to rise to 24.8 percent of GDP by 2033, substantially above the 50‐year average of 21.0 percent. Reducing spending to the long‐term average would restrain debt to about 100 percent of GDP.

Entitlement and Federalism Reform Plan

Policymakers should balance the budget and cut debt in the long term, but a good near‐term goal would be to stabilize the debt at 100 percent of GDP. The plan proposed here would achieve that in 2033 by reducing spending to 21.1 percent that year.

The table shows proposed spending reforms. The entitlement reforms would be enacted in the near‐term and the savings would increase over time, while the federalism reforms would be phased in over 10 years. The reforms would cut program spending by $1.31 trillion in 2033 and cut overall spending including interest by $1.45 trillion, or about 15 percent of baseline spending that year.

The entitlement reforms include limiting Medicare’s growth rate to the growth rate of GDP beginning in 2026. A good way to achieve that would be to restructure the program around individual vouchers, which would improve choice, encourage competition, and restrain costs. For Medicaid, the plan would convert today’s open‐ended matching grants to fixed block grants in 2024, which would control federal costs while freeing the states to innovate with their health care systems.

For Social Security, the table includes two straightforward reforms, as estimated by CBO. The first modestly reduces the annual cost of living (COLA) adjustment for benefits, and the second would modestly raise the program’s full retirement age. (For both reforms, I estimated 2033 savings based on the CBO figures for 2032).

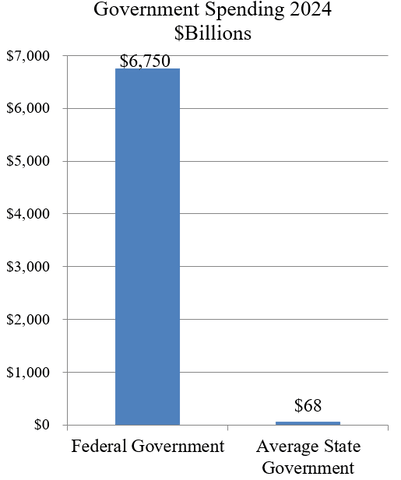

The federalism reforms would cut federal aid‐to‐states for programs administered by state and local governments. The federal government spends $1 trillion a year on more than 1,300 aid‐to‐state programs. The aid system ties the states into regulatory knots, undermines democratic control, destroys accountability, and generates waste, fraud, and abuse. State and local governments should fund their own programs for welfare, housing, transit, education, and many other things.

For programs in the table, the plan would phase in the federalism reforms over 10 years. The states could respond by funding their own programs if they chose, either by raising taxes or creating budget room by cutting other spending. Without all the top‐down rules imposed by Washington, stand‐alone state programs would likely be leaner and more efficient.

Final Thoughts

Policymakers may think such spending reforms are radical, but larger reforms have succeeded abroad. Facing a debt crisis in the 1990s, Canada cut its federal spending from 23 percent of GDP in 1993 to just 15 percent by 2006. The government cut entitlements, business subsidies, defense, aid to the provinces, and many other things. It privatized assets such as airports and the air traffic control system. As the government was cut, the Canadian economy boomed for 15 years.

America needs similarly large spending cuts. In addition to the above reforms, we should cut business subsidies, farm subsidies, foreign aid, and energy subsidies. We should also privatize federal assets.

I discuss further reforms here and Romina Boccia proposes reforms here and here.

____________________________________________

Data Notes: the federalism reforms generally involve zeroing out aid to the states for the specified activities. The K‑12 subsidies do not include special education subsidies. The excess highway aid is projected highway outlays that are greater than highway trust fund revenues. The values in the table were sourced from CBO projections and OMB projections.