The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just released an update to its 10‐year fiscal projections. CBO highlights higher inflation, lower revenues, and higher spending than previously projected.

CBO’s report arrives as the debate over the debt ceiling heats up in light of an early June deadline. House Republicans passed their opening bid to raise the debt ceiling by $1.5 trillion or through March 2024, whichever comes first. The Limit, Save, Grow Act would save $4.8 trillion, reducing the 10‐year spending total by 6 percent. So far, President Biden and most Congressional Democrats have refused to negotiate, demanding a so‐called clean debt ceiling increase—despite strong precedent in U.S. history for pairing debt limit increases with policy reforms to address rising debt. According to Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen, federal borrowing authority could run out by June 1.

Lawmakers ought to heed the CBO’s latest update. The responsible choice is to raise the debt limit in combination with fiscal reforms that begin to stabilize federal debt as a percentage of GDP (gross domestic product). A Better Budget Control Act which enforces a single, total limit on discretionary spending, accounts and pays for emergency spending, and sets up an independent nonpartisan commission to reform Medicare and Social Security would allow Congress to responsibly raise the dollar‐denominated debt limit without further inflating the public debt as a share of the economy.

The following are the key trends outlined in CBO’s report:

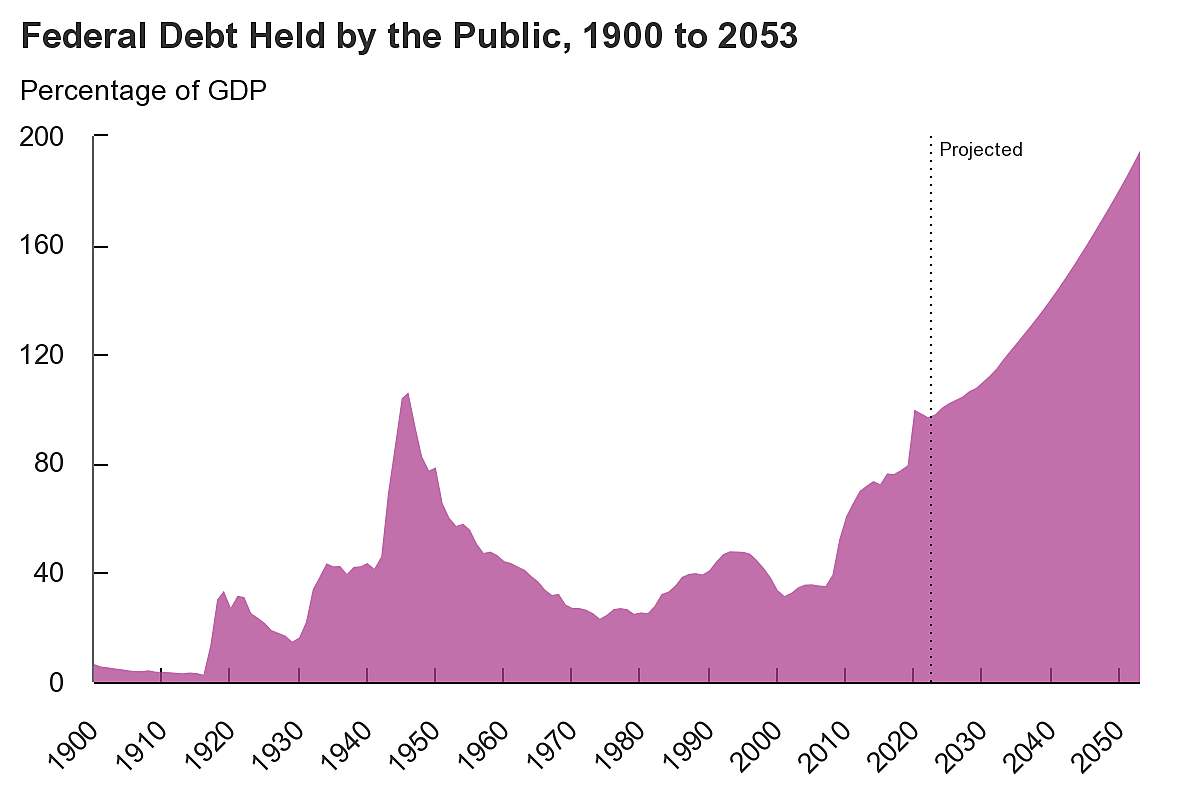

Debt will grow to 119 percent of GDP

Federal publicly held debt (the debt the United States has borrowed from credit markets) is currently $24.6 trillion. As a percentage of the country’s yearly economic output, public debt will be 98.2 percent of GDP by the end of 2023. By 2028, public debt will surpass its all‐time World War II high of 106 percent of GDP. By 2033, public debt will rise to 118.9 percent of GDP. See the CBO graph above for historical context and additional longer‐term debt projections. That’s about 0.6 percent or 264 billion more than CBO projected just three months earlier.

According to a recent paper published by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), CBO may be underestimating the potential growth in debt, deficits, and spending. CBO assumes that many key variables, such as real interest rates, health care cost, and economic growth, will continue based on past trends. Under AEI’s alternative projection, “these variables are outcomes produced by supply and demand, based on logical functional forms and deep parameter estimates from the literature or empirical analysis.” Their model results in the debt‐to‐GDP ratio reaching 132 percent by 2032.

High and rising debt slows economic growth, increases interest rates, and crowds out private investment. These negative economic effects will only worsen as the United States’ fiscal trajectory deteriorates. If the United States continues to unsustainably accumulate debt, it raises the risk of a sudden fiscal crisis where bond holders lose confidence in the federal government’s ability or willingness to service debt without inflating away the debt’s value by reducing the purchasing power of the national currency.

Rising entitlement spending is the main cause of widening deficits

In 2022, the budget deficit was $1.4 trillion, about $340 billion more than CBO originally projected. The difference can primarily be attributed to the Biden administration’s costly student debt relief policy. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget now puts the total cost of Biden’s student loan policies at $970 billion. This includes student debt policies implemented or proposed since the pandemic, such as “$400 billion from debt cancellation, $230 billion from the Administration’s new IDR program, nearly $200 billion from the student debt pause, and almost $150 billion from a variety of other actions,” according to Marc Goldwein. CBO projects the deficit to continue to widen to an average $2 trillion or 6.1 percent of the GDP over the 2024 to 2033 period. The average non‐crisis deficit, post‐Great recession and pre‐pandemic, was about 4 percent of GDP.

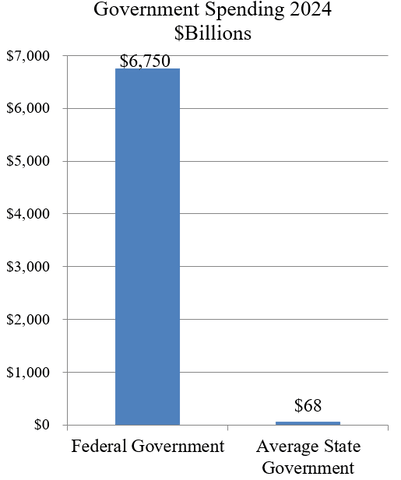

Elevated spending is the root cause of increasing deficits. While emergency pandemic spending and student loan policies have driven recent deficit increases, CBO expects major entitlements including Social Security and federal health care programs to be responsible for the lion’s share of future spending. From 2023 to 2033, Social Security spending will grow from $1.3 trillion to $2.4 trillion, an increase of 85 percent. Major health care programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, will grow from $1.7 trillion to $3.1 trillion over the same period. Combined, major entitlements will be responsible for 60 percent of total spending growth over the next 10 years. In total, the 10‐year projected cost of major entitlements has risen by $153 billion since CBO’s February report.

Rising interest costs worsen fiscal outlook

As the government borrows more, interest costs will rise. This borrowing cost, expressed as net interest cost in the budget, is the second largest driver of rising spending after major entitlements. This year, CBO projects net interest costs to total $640 billion, consuming 13 percent of federal revenues for 2023. In just 10 years, net interest costs are projected to reach $1.4 trillion, consuming 20 percent of federal revenues for 2033. For context, interest costs will exceed total annual discretionary defense spending by 2028 and nondefense discretionary spending by 2031. Compared to CBO’s February projections, 10‐year interest costs have risen by $131 billion due to increases in the actual rates paid on recently issued Treasury securities and an increase in expected 10‐year deficit spending. Were interest rates 1 percentage point higher than currently projected interest costs would rise to nearly $2 trillion by 2033, for a cumulative interest cost increase of $3 trillion over 10 years.

In addition to putting the United States deeper in the hole, rising interest costs could place budgetary constraints on Congress. As interest costs consume a larger share of federal revenues, legislators will have fewer taxpayer dollars remaining to fund other critical spending priorities like defense.

Economic trends worsen while spending increases

CBO projects higher inflation than it did in February, increasing its projections of net interest spending by $131 billion over the 2023 to 2033 period. CBO also reduced its short‐term projections for government revenue and economic output to reflect lower economic growth. In April of this year alone, the government collected $250 billion less in taxes than expected. One major uncertainty is the President’s student loan policy, currently under review by the Supreme Court. Biden’s proposed income‐driven repayment plan for student loans would add $111 billion to deficit spending over the next decade — this policy was not included in CBO’s latest outlook. However, if the Supreme Court rules against President Biden’s student loan debt forgiveness, this could reduce deficits by $400 billion over the next decade. In total, net spending projections for 2023 to 2033 increased by $234 billion.

Fiscal guardrails can create a sustainable fiscal future

CBO’s updated baseline projections should give lawmakers across the political spectrum cause for concern. High and rising public debt increases the risk of a sudden fiscal crisis, constrains the government’s ability to respond to unforeseen emergencies, and slows economic growth. In the last three months alone, the fiscal and economic outlook has changed enough to warrant worsened 10‐year budgetary projections. CBO’s revised projections may still be too optimistic. CBO does not account for the possibility of a major military conflict, financial crisis, or public health emergency over the next decade. Any of these crisis events could significantly increase spending, widen deficits, and further add to the public debt.

Congress and the President ought to consider a Better Budget Control Act to reduce inflationary pressures and limit the risk of a future fiscal crisis. New limits on discretionary spending, immediate reductions to mandatory programs, and future savings from reforms to Medicare and Social Security put forth by an independent commission can stabilize the federal debt, by saving at least $8 trillion over the next 10 years. Such an agreement would signal to markets that the federal government intends to be a sound fiscal steward, which would enhance confidence in U.S. policymaking. Greater confidence would boost economic growth and American incomes. By reducing uncertainty over future tax increases and inflation, Congress can unleash greater investment.

Legislators should work together to avoid a future fiscal crisis by reducing spending and adopting prudent budgetary reforms as they confront the debt limit this year.