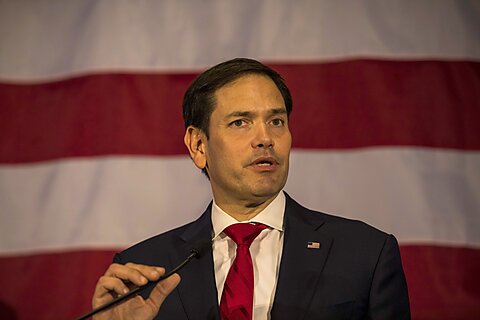

Writing in National Affairs, Senator Marco Rubio (R‑FL) recently made the case for a more vigorous—some might even say intrusive—government role in encouraging the development of US manufacturing. Such an effort, Rubio claims, is necessary to ensure the United States is not beholden to foreign actors for critical goods. While the importance of manufacturing to national security shouldn’t be discounted, realizing Rubio’s vision would entail a vast expansion of government power in pursuit of addressing a problem that is, at best, greatly overstated.

Perhaps more importantly, the essay suffers from errors of both fact and logic that call into question his premises and overall proposal. Here’s a closer look at eight myths that undergird the Florida senator’s call for robust industrial policy and the reality behind them.

Myth 1. U.S. manufacturing has crumbled. Rubio’s call for more muscular government intervention to rebuild domestic manufacturing implies the sector is in dire straits. Rubio twice references the “collapse of American manufacturing,” necessitating what he describes as a “serious effort to rebuild American industry.” But his entire premise is wrong. Domestic manufacturing is doing pretty well.

Whether measured in terms of value‐added or output, US manufacturing is at or not far off from record highs. The United States accounts for a greater share of global manufacturing output than any country save China, with more output than Germany, India, Japan, and South Korea combined. US manufactured goods exports in 2022 totaled nearly $1.6 trillion, including tens of billions worth each of autos, medical instruments, integrated circuits, and aerospace. In 2021, the United States was the world’s fourth‐largest steel producer, second‐largest automaker, and largest aerospace exporter.

To be sure, American manufacturing has experienced a decline in employment even while output has increased. This mostly reflects productivity improvements—the sine qua non of rising living standards—that allow US firms to produce more with fewer workers. The US steel industry, for example, saw production rise by 8 percent from 1980 to 2017 even while steel employment over the same period declined by 79 percent (399,000 to 83,000).

American manufacturing may be many things, but a sector in collapse—or anything close—it is not.

Myth 2. Declines in manufacturing employment led to widespread social problems. Rubio’s inaccurate claims about manufacturing feed into another argument: that the sector’s alleged decimation is responsible for wider societal ills, such as declining marriage rates and childbearing. Even if one (very generously) grants that Rubio’s armchair theorizing accurately diagnoses falling manufacturing employment as a key driver of such trends, it’s unclear to what policy conclusions this leads.

Given that the primary explanations for declining manufacturing employment are productivity growth, and technology‐related trends such as dematerialization rather than trade (notably, China Shock authors David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson state in a 2017 paper that their analysis “does not imply that surging import competition from China over the last two decades has been the sole or primary driver” of the changing structure of marriage and childbirth), how does Rubio propose putting those genies back in their respective bottles? A reversion to productivity levels (and, necessarily, living standards) of past decades seems no kind of desirable (or workable) solution. Exactly what should come next, even assuming Rubio’s thesis is correct, is unclear.

Indeed, any notions that a manufacturing renaissance would reverse falling rates of childbearing, for instance, must reckon with the fact that China—by far the world’s leading manufacturing country—is struggling with its marriage and birth rates. The country is hardly alone, with birth rates falling around the world. And if a lack of manufacturing employment lies behind many societal ills, how is that reconciled with the nearly 600,000 manufacturing job openings that existed as of February? Such jobs are certainly out there for those with the desire and qualifications for them.

Myth 3. The Biden administration has gotten industrial policy wrong, but we can do it right. Rubio blasts the Biden administration for alleged missteps in its industrial policy efforts, arguing that they “reek of special‐interest favoritism and progressive ideological capture” and have been self‐sabotaged by “burdensome regulations, red tape, and activist mandates.” Maintaining that such outcomes are not an industrial policy inevitability, Rubio claims they can be remedied by “identify[ing] the Biden administration’s particular failures, which are not endemic to industrial policy broadly [emphasis added], and [correcting] them with conservative insights.”

But even if one grants that Rubio and his fellow Republicans possess unique gifts that allow them to deftly implement industrial policy and enjoy special immunity from activist forces—a proposition that warrants deep skepticism—such thinking is still fatally flawed. Unless Rubio has a plan to permanently exile Democrats from office, they are bound to spend significant amounts of time manipulating the industrial policy machinery that Rubio seeks to implement. The ship of state will inevitably be steered by people whose views and policy goals sharply contrast with those of Rubio and his fellow travelers. And what then?

Myth 4. Industrial policy has an easy and obvious limiting principle. One of Rubio’s rationales for industrial policy is the need to ensure the domestic production of “goods that are essential to maintaining a free and prosperous republic.” Hearkening back to the country’s earliest days, Rubio notes that Alexander Hamilton “favored using subsidies to foster domestic manufacturing and ‘render the United States, independent on foreign nations, for…essential supplies’” and highlights the use of a national arsenal to produce “small arms that made our nation less reliant on foreign powers for defense.”

This starts to sound pretty reasonable. Rubio doesn’t want to require that everything be American‐made but rather just those items that are essential. However, even leaving aside that, as noted in the above table, US production of defense‐related goods has expanded significantly since the 1990s, the Florida senator has a tellingly expansive view of what that entails. Among those sectors he places in this category are “mining, oil and gas, metallurgy, agriculture, chemistry, medicine, etc [emphasis added].” These are not bit players in the US economy, and it’s easy to see how other industries—after extensive lobbying, of course—could also find themselves deemed “essential.” In this regard, it’s worth recalling that Rubio has previously argued US sugar protectionism is a national security issue.

In reality, “essential” can mean almost anything and surely means different things to different people. Anyone with a modicum of ability to manipulate the levers of government would have a field day bending the term to their desired ends. Recall, for example, that the Trump administration deemed imports of low‐value steel from close allies to threaten national security. No great imagination is required to envision Rubio’s industrial policy designs becoming a Trojan Horse for politicians of every stripe, including those with views antithetical to his own.

5. China’s economic might is the result of industrial policy and the United States must depart from market economics to address the country’s challenge. While fear of China animates much of Rubio’s call for industrial policy measures, he also evinces at least a certain grudging respect for the country’s accomplishments. As he states:

Our adversaries are implementing ambitious industrial strategies to take advantage of this moment. The phrases “Made in China 2025” and “Military‐Civil Fusion” denote Beijing’s plan to use industrial dominance to displace and degrade the United States. Even if we dismiss Beijing propagandists’ exaggerated claims about this strategy’s success and account for the waste and corruption endemic to China’s communist system, it’s hard to argue with the results: While our industrial base has shrunk, China’s has grown many times over.

Indeed, our greatest adversary is now the world’s largest ship‐ and steel‐making power by several orders of magnitude. It’s the world’s largest producer and exporter of cars. It seeks to become the number‐one producer of microchips and aerospace technology as well, though it has been denied the top spot for now.

China’s economy and manufacturing sector have indeed grown by leaps and bounds in recent decades. Where Rubio errs, however, is in highlighting this impressive performance while failing to note its correlation with significant market liberalization. Centrally‐planned Chinese attempts at industrialization under the Communist Party are nothing new, going at least as far back as the Great Leap Forward’s employment of millions of backyard furnaces to smelt steel. That didn’t work. Proving more fruitful has been the paring back of laws that inhibited the dynamism and innovation of private enterprise.

Regarding China’s primacy in areas such as automaking and shipbuilding, there is no doubt that the country’s government has firmly placed its thumb on the scale through the employment of export credits and other subsidies. But that’s far from the entire story. For example, China is—by some distance—the world’s largest auto market. Logically, it should also be home to a sizeable amount of automaking given the propensity of manufacturers to serve domestic markets.

Similarly, the world’s second‐most populous country is not just a leading steel producer but also a massive consumer of it as well.

It’s also not a great surprise that China is a dominant shipbuilder given its success in related manufacturing sectors, such as steel (a key shipbuilding input). Even as far back as the 1980s predictions were being made that China would supplant South Korea as a shipbuilding leader.

None of this is to deny that certain policy measures may have benefitted particular industries. Perhaps they have even played a decisive role. But it should also be recognized that the story goes beyond industrial policy and that such policies have produced many downsides.

A 2019 study, for example, found that China’s shipbuilding industry received 550 billion renminbi (RMB)—approximately $80 billion at the time—in government support between 2006 and 2013, but that these subsidies generated only 145 billion RMB ($21 billion) of net profit for domestic producers. Furthermore, a large share of the subsidies (230 billion RMB/$33 billion) benefitted mostly non‐Chinese global ship owners in the form of lower ship prices. These subsidies may have artificially expanded the size of China’s shipbuilding industry but at a significant economic cost.

Such costly adventures in industrial policy contribute to the corruption, debt, low productivity, malinvestment, overcapacity, youth unemployment, fading consumer, foreign investor confidence, and other economic and social problems facing China today. Notably, Rubio himself begrudgingly acknowledges China’s current economic challenges (“China may yet collapse under the weight of its own contradictions”) yet ignores industrial policy’s role in creating many of them.

More generally, there should be a great wariness about taking economic lessons from a country whose per capita GDP is roughly one‐sixth that of the United States.

Myth 6. Deregulation is industrial policy too. One high point of Rubio’s essay is his recognition of the costs imposed by runaway red tape and his embrace of deregulation to boost US competitiveness. His insistence that “deregulation is industrial policy,” however, is misguided. As my colleague Scott Lincicome has documented, both advocates and critics agree that “industrial policy” has certain requisite elements, but these do not include broad (“horizontal”) policies such as corporate tax rate reductions or regulatory reform. In general, industrial policy entails governments targeting specific domestic manufacturing companies, industries, or products for special treatment (subsidies, tariff protection, etc.) to beat the market and achieve certain national objectives. If reforming, say, the National Environmental Policy Act were to fall under the banner of “industrial policy,” then the term would lose all meaning.

That said, any talk about US economic revitalization should certainly use deregulation as a starting point. Before dreaming up new laws and spending initiatives to implement industrial policy, legislators like Rubio should first examine what existing policies—including regulations—are holding US industries back.

Myth 7. Foreign “reliance” is always dangerous. Strongly implied in Rubio’s essay is the notion that turning to foreign sources to meet “vital” and “essential” US needs is inherently dangerous. True security, goes the thinking, can only be found in self‐reliance. But this rests upon questionable logic. Canada and China are both foreign countries yet assigning them similar risk profiles would seem an obvious mistake.

Should Americans be concerned, for example, that Canada—a longtime NATO ally with whom the United States shares the world’s longest undefended border—is overwhelmingly the top source of imported aluminum? Probably not. Yet Rubio gives little indication of seeking to distinguish between different countries, instead relying on a vastly oversimplistic foreign‐domestic dichotomy. Furthermore, it’s not apparent how great the risk is even for countries with whom the United States enjoys less than cordial relations.

As one 2023 paper found, even in those limited sectors where the United States finds itself dependent on non‐friendly countries for critical items, experience during the COVID-19 pandemic suggested that “countries regarded as non‐friendly alleviated rather than caused critical bottlenecks.”

Far from advancing US national security interests, policies rooted in US self‐reliance often undermine it. Eschewing more efficient sourcing from US allies and partners means overpaying, in turn harming the US economy and—in the case of defense outlays—generating less bang for the national security buck. Furthermore, access to foreign goods from geographically diverse sources provides critical redundancies (as seen, for example, during 2022’s baby formula shortage). Far from strengthening the United States, blocking access to foreign products in many instances makes the country poorer and weaker.

Of course, this is not to suggest that risk should have no bearing on US sourcing decisions. Even if attractive from a cost perspective, the US military shouldn’t purchase naval vessels from Chinese shipyards. But neither should this mean that vast swathes of foreign goods should automatically be placed off‐limits. Free and open trade—particularly with trusted partners and allies—should be the default position and a high bar placed on any deviation.

Myth 8. Government can “get out of the way” and still allow industrial policy to work its magic through private enterprise. Laudably, Rubio concedes that waste and abuse is an industrial policy inevitability. He argues, however, that it can be minimized by “thinking clearly about the incentives that public funding creates and establishing enforceable metrics.” As he elaborates:

We can do this without dictating to companies how to invest and compete in minute detail. Instead, our standards should focus on what companies must accomplish (i.e., meeting meaningful production benchmarks) and whom those accomplishments must benefit (i.e., the American people). Establishing clear expectations and rewards and then getting out of the way is the right tack here.

The problems here are obvious. For starters, production benchmarks—even “meaningful” ones—can mask real business successes or failures (e.g., productive companies that went years without making a profit) and can also be easily manipulated (e.g., “research” tax credits). Furthermore, if an industry policy initiative can continue by merely benefiting the “American people”—a subjective standard if there ever was one—then oversight would surely be problematic. No great difficulty is required to see how lobbyists and other self‐interested parties could use such language to their advantage, or how politicians who’ve staked their reelection or legacies on the success of an industrial policy project could work to keep it going long after failure has become obvious. (Both problems, in fact, are common to U.S. industrial policies.)

Indeed, if this is the best standard that Rubio could construct in a piece advocating for industrial policy, what kind of language might we expect when such initiatives are hashed out in Washington backrooms?

Rubio wants to have his industrial policy cake and eat it too, effectively combining the federal government’s power and resources with private sector know‐how and innovation—all with minimal waste. But doling out money to private sector actors with vague instructions to meet random benchmarks and benefit the “American people” is a standard ripe for exploitation—exploitation we’ve seen time and time again with US industrial policy. Conversely, strict oversight by an oft‐plodding bureaucracy brings with it attendant downsides. Such tradeoffs cannot be avoided.

Summing up: Senator Rubio admits that waste and abuse are inevitable byproducts of industrial policy. He maintains, however, that they can be minimized provided that—as he wrote in a condensed version of his thesis published in the Washington Post last week—we “get industrial policy right.” But how can Rubio be trusted to get industrial policy right when his essay championing it gets so much wrong?