Tomorrow, the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (ENR) will hold a confirmation hearing for three new nominees to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)—David Rosner, Lindsay See, and Judy Chang. If confirmed, these nominees would represent a majority of votes on the five‐commissioner panel and help shape the future of electricity and natural gas regulation in America.

The best (read: least bad) option from a libertarian perspective is for the future commissioners to uphold FERC’s organic statutes. In these statutes from the 1930s—the Federal Power Act (FPA) and the Natural Gas Act (NGA)—Congress has already answered the major policy questions that have plagued FERC in recent years, including the question of whether FERC should continue to approve natural gas pipelines despite their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (so long as there are willing natural gas customers, the answer is yes).

Based on my reading of the FPA and NGA, Congress dictated that (1) electricity should be reliable and available at just and reasonable rates, and (2) supplying natural gas to American consumers is in the public interest. These two statutes are complementary—without abundant natural gas, electricity will be unreliable, and electric rates will cease to be just and reasonable. The free market could do this on its own without federal regulation, but so long as public utility regulation exists, these organic statutes can be a bulwark against activist agencies.

To be clear, Congress—not to mention state governments across the country—can and should do more to free energy policy in the United States. Today’s energy policy is far from ideal, particularly from the free‐market perspective. Still, administrative agencies like FERC should avoid overstepping their statutory bounds and subjecting energy markets to unnecessary intervention and political uncertainty. Paraphrasing Hippocrates, FERC nominees should “first, do no harm.”

Abundant Natural Gas and the “Public Interest”

The purpose of the NGA is to promote natural gas delivery to consumers. NGA section 1(a) states that “the business of transporting and selling natural gas for ultimate distribution to the public is affected with a public interest, and that Federal regulation in matters relating to the transportation of natural gas and the sale thereof in interstate and foreign commerce is necessary in the public interest.” The opening line of Section 1(a) refers to a Federal Trade Commission Report finding that federal regulation should ensure an adequate natural gas supply at fair, nondiscriminatory prices.

The existence of the terms “public interest” and “public convenience and necessity” in the NGA does not give FERC license to redefine those terms on a whim. However, that is precisely what FERC attempted to do just two years ago. In February 2022, FERC issued two related policy statements that dramatically departed from decades of natural gas permitting policy (an Updated Policy Statement on Certification of New Interstate Natural Gas Facilities and an Interim GHG Policy Statement).

A major policy change was the redefinition of the term “public interest” to reflect the climate focus of the chairman at the time. In other words, because the chairman deemed climate change an “existential threat” (his words), any definition of the public interest should surely include it.

Other commissioners vehemently disagreed. Quoting NAACP v. FPC, former Commissioner James Danly wrote in his dissent, “‘public convenience and necessity’ means ‘a charge to promote the orderly production of plentiful supplies of electric energy and natural gas at just and reasonable rates.’” Senators agreed with Danly. The new policies were so far off base that, once confronted by Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee members, FERC withdrew the policy statements and labeled them as “drafts.”

The February 2022 policy statements could be reinstated at any time. However, such uncertain policies reduce the development of natural gas infrastructure. When FERC withholds, slows, or redefines key terms in reviewing proposed natural gas pipeline projects, it contravenes its congressional mandate to ensure plentiful gas supplies at a reasonable cost. It also undermines the very markets it was created to protect (even though such protection is unnecessary and, indeed, often undermined by regulators). In contrast, by allowing natural gas to compete against other energy sources on its merits, FERC can help ensure that markets and consumer choice drive America’s energy future.

Gas‐Electric Nexus: A Reliable, Affordable Grid Requires Abundant Natural Gas

FERC’s statutory responsibility for grid reliability was reinforced by Congress in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which added a new Section 215 to the Federal Power Act to bolster FERC’s ability to improve grid reliability in the wake of the August 2003 blackout. Section 215 requires FERC to certify an Electric Reliability Organization (ERO) that creates mandatory reliability standards. FERC selected the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) as the ERO.

NERC repeatedly has observed that “[w]ith increasing levels of variable renewable generation in the resource mix, there is a growing need to have resources available that can be reliably called upon on short notice to balance electricity supply and demand if shortfall conditions occur.” Last year, as a result of the policy‐driven expansion of intermittent renewables in the United States, NERC in 2023 identified energy policy as a top risk to electric reliability.

Given FERC’s statutory duty to protect grid reliability under the FPA, it should promote a robust natural gas infrastructure and avoid contributing to the reliability risks identified by NERC. Natural gas infrastructure is not only supported by the plain text of the NGA, it is a prerequisite for the reliable electricity at just and reasonable rates demanded by the FPA.

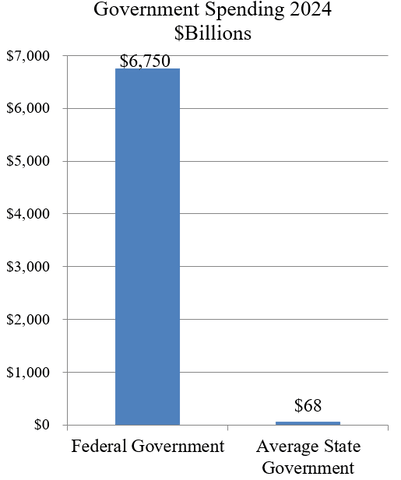

Under the FPA, FERC has a dual mandate to ensure just and reasonable rates in addition to reliability. To put it bluntly, restrictions on natural gas supply will raise electricity prices for consumers in America. The following graph from the 2017 Department of Energy Staff Report to the Secretary on Electricity Markets and Reliability illustrates the historical trend:

(Source.)

Wholesale electricity prices closely track natural gas prices. And as one might expect, regional electricity prices track even more closely with regional natural gas hub prices. Consumers benefit from the unrestricted flow of resources, including natural gas, and abundant natural gas significantly reduces the wholesale cost of electricity relative to supply‐constrained areas.

Major Question: Will SCOTUS Make FERC Textualist Again?

On June 30, 2022, the Supreme Court ruling in West Virginia v. EPA applied the Major Questions Doctrine to the EPA, finding that the agency lacked clear direction from Congress to issue its Clean Power Plan. The Supreme Court ruling was a shot across the bow of administrative agencies and suggested that the trend of agencies deciding major public policy questions on their own was coming to an end.

As discussed above, on February 18, 2022, FERC attempted to decide a major policy question when it reimagined the statutory meaning of the “public interest” under the NGA. As another example, the FERC homepage reads in prominent type “Shaping the Grid of the Future.” This proactive posture is inappropriate for a creature of statute that Congress never tasked with shaping anything.

Others have taken notice. In 2022, American Enterprise Institute scholar Ben Zycher described FERC’s recent actions as “increasingly ad hoc, ill‐defined, politicized, driven by decision criteria far outside FERC’s actual areas of expertise, and certain to display shifting standards over time.”

Perhaps the most critical policy question before FERC is whether to attempt—once again—to give itself climate authorities Congress never granted. Commissioner Mark Christie noted in his dissent against the now‐draft policy statements that there is no textual support in the NGA for FERC to deny a pipeline application due to potential upstream and downstream GHG emissions.

Commissioner Christie wrote: “Whether this Commission can reject a certificate based on a GHG analysis—a certificate that otherwise would be approved under the NGA—is undeniably a major question of public policy. It will have enormous implications for the lives of everyone in this country, given the inseparability of energy security from economic security.”

Cato intern Zoe Galinsky contributed to this article.